Compiler Design

A compiler, as a black box, converts source code to an executable program on a specific platform.

The executable program could be machine code for a specific CPU architecture (e.g., x86, ARM) or bytecode for a virtual machine (e.g., JVM, Python VM).

Compilers are typically split into frontend and backend.

- The frontend is responsible for:

- Understanding the semantics of the program

- Converting the source code into an Intermediate Representation (IR) that semantically describes the behavior of the program.

- The backend is responsible for:

- Translating the Intermediate Representation into an executable program.

The diagram above illustrates the overall concept of dividing the compiler into distinct phases.

Different languages may output different structures for each phase; some may omit certain phases altogether (e.g., IR generation and machine-independent optimizations not present in the old Kotlin compiler); some might perform the IR generation phase as part of the Backend synthesis (e.g., the new Kotlin compiler); etc.

Nevertheless, the idea of separating the compiler into analysis and synthesis phases is universal.

For markup languages, such as HTML, or Markdown, or human-readable data-interchange formats, such as JSON, or TOML, it does not make sense to speak about compilation.

However, IDE and other tools may apply the same lexical, syntax, and semantic analysis phases to verify the correctness of the format and to provide a better developer experience.

Lexical analysis (lexing/scanning/tokenizing)

Lexers are generally quite simple, with most of the complexity deferred to later phases of the compiler. The output of the Lexer is just a series of tokens.

For example, the following Kotlin file:

package sample.hello

fun hello(user: String) = "Hello, $user"

would be converted into the following stream of tokens:

PACKAGE("package")

WS(" ")

Identifier("sample")

DOT(".")

Identifier("hello")

NL("\n")

NL("\n")

FUN("fun")

WS(" ")

Identifier("hello")

LPAREN("(")

Identifier("user")

COLON(":")

Inside_WS(" ")

Identifier("String")

RPAREN(")")

WS(" ")

ASSIGNMENT("=")

WS(" ")

QUOTE_OPEN(""")

LineStrText("Hello, ")

LineStrRef("$user")

QUOTE_CLOSE(""")

Different languages might have various strategies for parsing tokens. However, languages are commonly described using Backus–Naur form (BNF), extended Backus–Naur form (EBNF), or a regex-like syntax, such as:

DIGIT=[0-9]

DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE = [_0-9]

DIGITS = {DIGIT} {DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE}*

HEX_DIGIT=[0-9A-Fa-f]

HEX_DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE = [_0-9A-Fa-f]

WHITE_SPACE_CHAR=[\ \n\t\f]

LETTER = [:letter:]|_

IDENTIFIER_PART=[:digit:]|{LETTER}

PLAIN_IDENTIFIER={LETTER} {IDENTIFIER_PART}*

ESCAPED_IDENTIFIER = `[^`\n]+`

IDENTIFIER = {PLAIN_IDENTIFIER}|{ESCAPED_IDENTIFIER}

FIELD_IDENTIFIER = \${IDENTIFIER}

EOL_COMMENT="/""/"[^\n]*

SHEBANG_COMMENT="#!"[^\n]*

INTEGER_LITERAL={DECIMAL_INTEGER_LITERAL}|{HEX_INTEGER_LITERAL}|{BIN_INTEGER_LITERAL}

DECIMAL_INTEGER_LITERAL=(0|([1-9]({DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE})*)){TYPED_INTEGER_SUFFIX}

HEX_INTEGER_LITERAL=0[Xx]({HEX_DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE})*{TYPED_INTEGER_SUFFIX}

BIN_INTEGER_LITERAL=0[Bb]({DIGIT_OR_UNDERSCORE})*{TYPED_INTEGER_SUFFIX}

LONG_SUFFIX=[Ll]

UNSIGNED_SUFFIX=[Uu]

TYPED_INTEGER_SUFFIX = {UNSIGNED_SUFFIX}?{LONG_SUFFIX}?

...

How tokens are defined is up to the language.

- In Java,

newis a keyword.- The lexer produces a special token representing the keyword.

- In Kotlin,

newis not a keyword.- The lexer parses it as an identifier, the same way it would parse

oldoremptyList.

- The lexer parses it as an identifier, the same way it would parse

Check out the Kotlin Flex lexer and Kotlin tokens.

Check out the Kotlin ANTLR lexer. Also Kotlin lexical grammar reference.

Check out the Kotlin lexical grammar specification.

Check out the Java lexical structure specification.

Syntax analysis (parsing)

The parser, in comparison to the lexer, is much more complex. It receives tokens from the lexer and produces a tree structure known as a syntax tree. Parsers are typically defined using a set of rules called grammar:

kotlinFile

: shebangLine? NL* fileAnnotation* packageHeader importList topLevelObject* EOF

;

script

: shebangLine? NL* fileAnnotation* packageHeader importList (statement semi)* EOF

;

shebangLine

: ShebangLine NL+

;

fileAnnotation

: (AT_NO_WS | AT_PRE_WS) FILE NL* COLON NL* (LSQUARE unescapedAnnotation+ RSQUARE | unescapedAnnotation) NL*

;

packageHeader

: (PACKAGE identifier semi?)?

;

importList

: importHeader*

;

importHeader

: IMPORT identifier (DOT MULT | importAlias)? semi?

;

importAlias

: AS simpleIdentifier

;

topLevelObject

: declaration semis?

;

typeAlias

: modifiers? TYPE_ALIAS NL* simpleIdentifier (NL* typeParameters)? NL* ASSIGNMENT NL* type

;

declaration

: classDeclaration

| objectDeclaration

| functionDeclaration

| propertyDeclaration

| typeAlias

;

...

Notice that the grammar references tokens from the lexer (EOF, NL, COLON, LSQUARE, RSQUARE, PACKAGE, IMPORT, DOT, MULT, …).

Whenever the lexer encounters the * character, it produces a MULT token. However, the lexer does not know whether the token represents a multiplication operation or a star import. It is the parser’s responsibility to disambiguate between the two.

The theory behind grammars and parsing is extensive and is usually covered in a full-semester university course.

Most programming languages (including markup languages like HTML) are defined by context-free grammar. In general, the two high-level approaches to parsing are:

- Top-down parsing (LL parsing)

- Starts from the top-level grammar rule and breaks it down to the input string.

- Generally easier to understand and implement, but may suffer from inefficiency or ambiguity issues with certain grammars.

- Bottom-up parsing (LR parsing)

- Starts with the input string and builds up to the top-level grammar rule.

- Often more powerful in terms of the grammars it can handle, but can be more complex to implement.

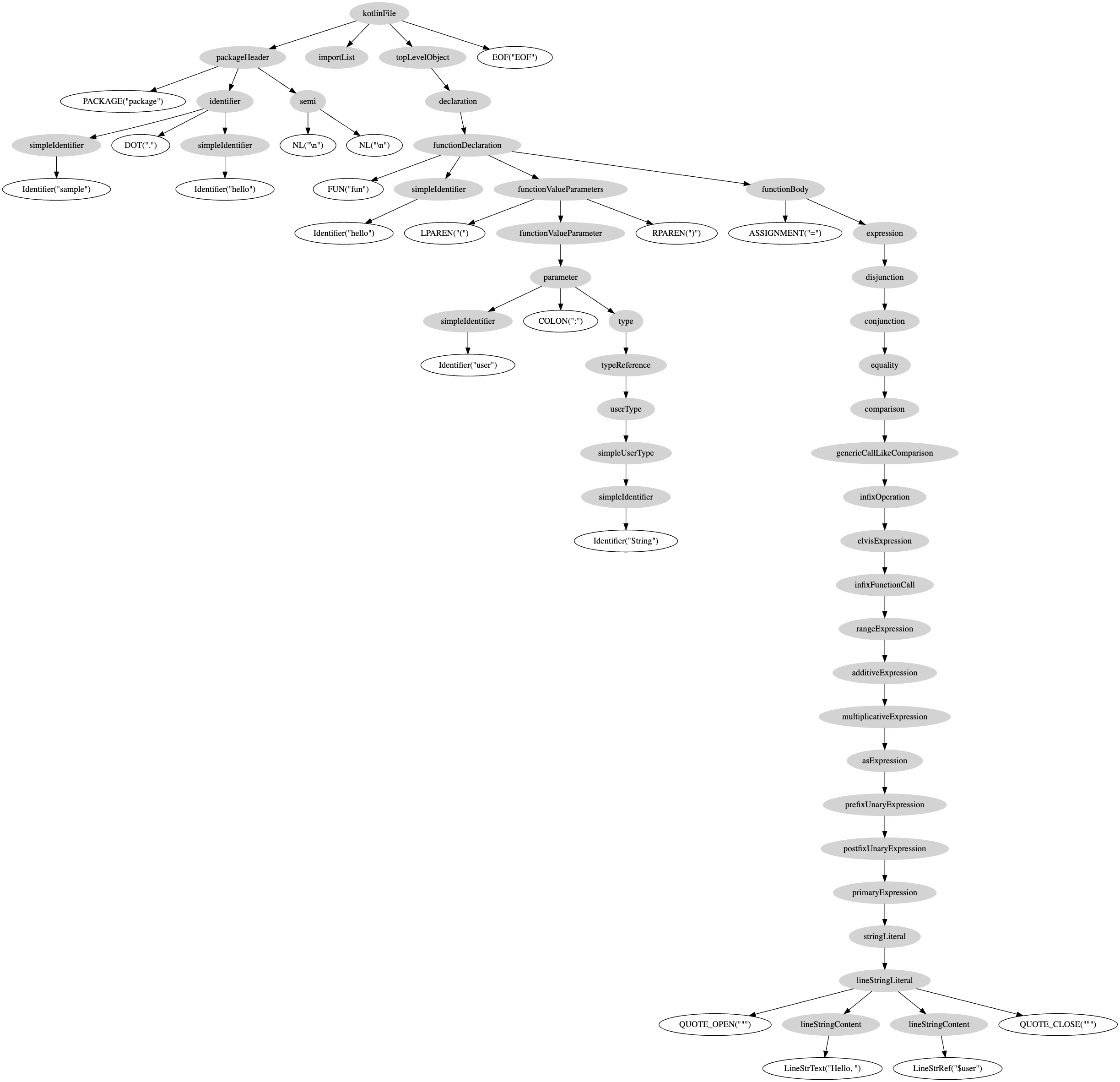

Using the Kotlin grammar rules, the following Kotlin file:

package sample.hello

fun hello(user: String) = "Hello, $user"

would be parsed into the following Parse tree:

Whitespace nodes are omitted for brevity.

Text

packageHeader

PACKAGE("package") <-- TOKEN

identifier

simpleIdentifier

Identifier("sample") <-- TOKEN

DOT(".") <-- TOKEN

simpleIdentifier

Identifier("hello") <-- TOKEN

semi

NL("\n") <-- TOKEN

NL("\n") <-- TOKEN

importList

topLevelObject

declaration

functionDeclaration

FUN("fun") <-- TOKEN

simpleIdentifier

Identifier("hello") <-- TOKEN

functionValueParameters

LPAREN("(") <-- TOKEN

functionValueParameter

parameter

simpleIdentifier

Identifier("user") <-- TOKEN

COLON(":") <-- TOKEN

type

typeReference

userType

simpleUserType

simpleIdentifier

Identifier("String") <-- TOKEN

RPAREN(")") <-- TOKEN

functionBody

ASSIGNMENT("=") <-- TOKEN

expression

disjunction

conjunction

equality

comparison

genericCallLikeComparison

infixOperation

elvisExpression

infixFunctionCall

rangeExpression

additiveExpression

multiplicativeExpression

asExpression

prefixUnaryExpression

postfixUnaryExpression

primaryExpression

stringLiteral

lineStringLiteral

QUOTE_OPEN(""") <-- TOKEN

lineStringContent

LineStrText("Hello, ") <-- TOKEN

lineStringContent

LineStrRef("$user") <-- TOKEN

QUOTE_CLOSE(""") <-- TOKEN

EOF("EOF")

Graphviz

digraph G {

a0 [label="kotlinFile",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a0 -> a1

a1 [label="packageHeader",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a1 -> a2

a2 [label="PACKAGE(\"package\")"]

a1 -> a3

a3 [label="identifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a3 -> a4

a4 [label="simpleIdentifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a4 -> a5

a5 [label="Identifier(\"sample\")"]

a3 -> a6

a6 [label="DOT(\".\")"]

a3 -> a7

a7 [label="simpleIdentifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a7 -> a8

a8 [label="Identifier(\"hello\")"]

a1 -> a9

a9 [label="semi",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a9 -> a10

a10 [label="NL(\"\\n\")"]

a9 -> a11

a11 [label="NL(\"\\n\")"]

a0 -> a12

a12 [label="importList",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a0 -> a13

a13 [label="topLevelObject",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a13 -> a14

a14 [label="declaration",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a14 -> a15

a15 [label="functionDeclaration",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a15 -> a16

a16 [label="FUN(\"fun\")"]

a15 -> a17

a17 [label="simpleIdentifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a17 -> a18

a18 [label="Identifier(\"hello\")"]

a15 -> a19

a19 [label="functionValueParameters",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a19 -> a20

a20 [label="LPAREN(\"(\")"]

a19 -> a21

a21 [label="functionValueParameter",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a21 -> a22

a22 [label="parameter",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a22 -> a23

a23 [label="simpleIdentifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a23 -> a24

a24 [label="Identifier(\"user\")"]

a22 -> a25

a25 [label="COLON(\":\")"]

a22 -> a26

a26 [label="type",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a26 -> a27

a27 [label="typeReference",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a27 -> a28

a28 [label="userType",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a28 -> a29

a29 [label="simpleUserType",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a29 -> a30

a30 [label="simpleIdentifier",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a30 -> a31

a31 [label="Identifier(\"String\")"]

a19 -> a32

a32 [label="RPAREN(\")\")"]

a15 -> a33

a33 [label="functionBody",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a33 -> a34

a34 [label="ASSIGNMENT(\"=\")"]

a33 -> a35

a35 [label="expression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a35 -> a36

a36 [label="disjunction",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a36 -> a37

a37 [label="conjunction",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a37 -> a38

a38 [label="equality",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a38 -> a39

a39 [label="comparison",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a39 -> a40

a40 [label="genericCallLikeComparison",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a40 -> a41

a41 [label="infixOperation",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a41 -> a42

a42 [label="elvisExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a42 -> a43

a43 [label="infixFunctionCall",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a43 -> a44

a44 [label="rangeExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a44 -> a45

a45 [label="additiveExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a45 -> a46

a46 [label="multiplicativeExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a46 -> a47

a47 [label="asExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a47 -> a48

a48 [label="prefixUnaryExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a48 -> a49

a49 [label="postfixUnaryExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a49 -> a50

a50 [label="primaryExpression",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a50 -> a51

a51 [label="stringLiteral",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a51 -> a52

a52 [label="lineStringLiteral",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a52 -> a53

a53 [label="QUOTE_OPEN(\"\"\")"]

a52 -> a54

a54 [label="lineStringContent",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a54 -> a55

a55 [label="LineStrText(\"Hello, \")"]

a52 -> a56

a56 [label="lineStringContent",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a56 -> a57

a57 [label="LineStrRef(\"$user\")"]

a52 -> a58

a58 [label="QUOTE_CLOSE(\"\"\")"]

a0 -> a59

a59 [label="EOF(\"EOF\")"]

}

The resulting parse tree is very verbose, containing all the intermediate grammar rules that are not useful for subsequent processing phases.

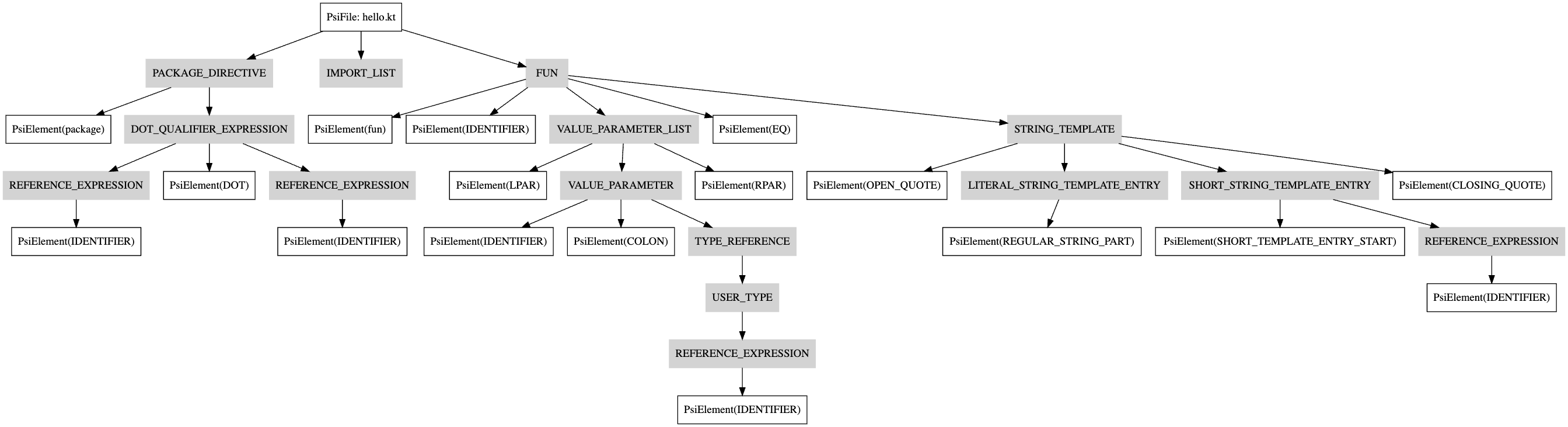

The parser then simplifies the parse tree to produce a Concrete Syntax Tree (CST). The CST omits details about how the tree was constructed and better represents the semantic structure of the program:

Whitespace nodes are omitted for brevity.

Text

PsiFile: hello.kt

PACKAGE_DIRECTIVE

PsiElement(package) <-- package

PsiWhiteSpace

DOT_QUALIFIER_EXPRESSION

REFERENCE_EXPRESSION

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- sample

PsiElement(DOT) <-- .

REFERENCE_EXPRESSION

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- hello

IMPORT_LIST

PsiWhiteSpace

FUN

PsiElement(fun) <-- fun

PsiWhiteSpace

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- hello

VALUE_PARAMETER_LIST

PsiElement(LPAR) <-- (

VALUE_PARAMETER

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- user

PsiElement(COLON) <-- :

PsiWhiteSpace

TYPE_REFERENCE

USER_TYPE

REFERENCE_EXPRESSION

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- String

PsiElement(RPAR) <-- )

PsiWhiteSpace

PsiElement(EQ) <-- =

PsiWhiteSpace

STRING_TEMPLATE

PsiElement(OPEN_QUOTE) <-- "

LITERAL_STRING_TEMPLATE_ENTRY

PsiElement(REGULAR_STRING_PART) <-- Hello,

SHORT_STRING_TEMPLATE_ENTRY

PsiElement(SHORT_TEMPLATE_ENTRY_START) <-- $

REFERENCE_EXPRESSION

PsiElement(IDENTIFIER) <-- user

PsiElement(CLOSING_QUOTE) <-- "

PsiWhiteSpace

Graphviz

digraph G {

node [shape=rect]

a0 [label="PsiFile: hello.kt"]

a0 -> a1

a1 [label="PACKAGE_DIRECTIVE",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a1 -> a2

a2 [label="PsiElement(package)"]

a1 -> a3

a3 [label="DOT_QUALIFIER_EXPRESSION",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a3 -> a4

a4 [label="REFERENCE_EXPRESSION",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a4 -> a5

a5 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a3 -> a6

a6 [label="PsiElement(DOT)"]

a3 -> a7

a7 [label="REFERENCE_EXPRESSION",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a7 -> a8

a8 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a0 -> a9

a9 [label="IMPORT_LIST",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a0 -> a10

a10 [label="FUN",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a10 -> a11

a11 [label="PsiElement(fun)"]

a10 -> a12

a12 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a10 -> a13

a13 [label="VALUE_PARAMETER_LIST",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a13 -> a14

a14 [label="PsiElement(LPAR)"]

a13 -> a15

a15 [label="VALUE_PARAMETER",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a15 -> a16

a16 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a15 -> a17

a17 [label="PsiElement(COLON)"]

a15 -> a18

a18 [label="TYPE_REFERENCE",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a18 -> a19

a19 [label="USER_TYPE",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a19 -> a20

a20 [label="REFERENCE_EXPRESSION",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a20 -> a21

a21 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a13 -> a22

a22 [label="PsiElement(RPAR)"]

a10 -> a23

a23 [label="PsiElement(EQ)"]

a10 -> a24

a24 [label="STRING_TEMPLATE",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a24 -> a25

a25 [label="PsiElement(OPEN_QUOTE)"]

a24 -> a26

a26 [label="LITERAL_STRING_TEMPLATE_ENTRY",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a26 -> a27

a27 [label="PsiElement(REGULAR_STRING_PART)"]

a24 -> a28

a28 [label="SHORT_STRING_TEMPLATE_ENTRY",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a28 -> a29

a29 [label="PsiElement(SHORT_TEMPLATE_ENTRY_START)"]

a28 -> a30

a30 [label="REFERENCE_EXPRESSION",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a30 -> a31

a31 [label="PsiElement(IDENTIFIER)"]

a24 -> a32

a32 [label="PsiElement(CLOSING_QUOTE)"]

}

The CST retains all the information from the original file, including whitespace, comments, semicolons, and parentheses, and can be used to fully reconstruct the original source code.

Successfully parsing a parse tree does not guarantee that the code represents a valid program.

For example, a parse tree might successfully represent total + 42, but it does not check whether the total variable is defined in the scope, nor does it verify whether the + operator is defined for types of total and Int.

Check out the kotlin-grammar-tools library to parse Kotlin code in a Java program.

Over the decades, many lexers and parsers have been created. Some of the most notable ones include:

Check out the Kotlin ANTRL parser and the Kotlin syntax grammar reference.

Check out the Kotlin syntax specification.

Check out the Java syntax specification.

Semantic analysis

During the semantic analysis phase, the compiler verifies that the Syntax Tree produced by the Parser semantically makes sense and is enhanced with semantic information.

- All imports are resolved (both implicit and explicit)

- All type references are resolved (both implicit and explicit)

- Variables are accessible within their scope

- Variables are properly initialized

- References are resolved

- Control flow is valid

- …

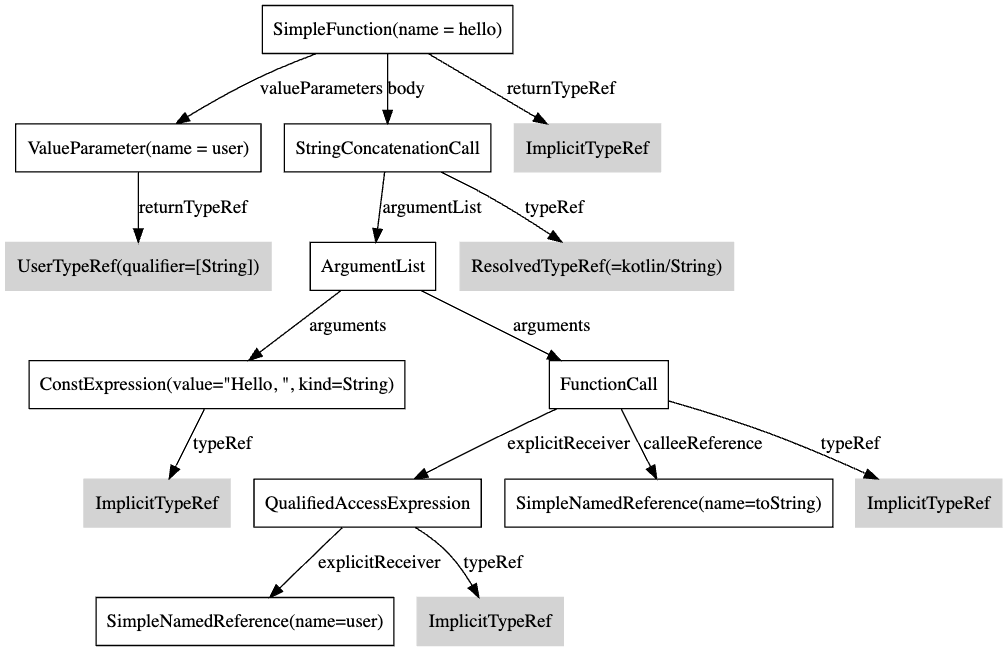

For example, the following Kotlin function:

fun hello(user: String) = "Hello, $user"

would be converted into the following Abstract Syntax Tree:

Text

SimpleFunction(name = hello) {

valueParameters = ValueParameter(name = user) {

returnTypeRef = UserTypeRef(qualifier=[String])

},

body = StringConcatenationCall {

argumentList = ArgumentList {

arguments = ConstExpression(value="Hello, ", kind=String) {

typeRef = ImplicitTypeRef

},

arguments = FunctionCall {

explicitReceiver = QualifiedAccessExpression {

calleeReference = SimpleNamedReference(name=user)

typeRef = ImplicitTypeRef

},

calleeReference = SimpleNamedReference(name=toString),

typeRef = ImplicitTypeRef

}

},

typeRef = ResolvedTypeRef(=kotlin/String)

}

returnTypeRef = ImplicitTypeRef

}

Graphviz

node [shape=rect]

a0 [label="SimpleFunction(name = hello)"]

a0 -> a1 [label="valueParameters"]

a0 -> a3 [label="body"]

a0 -> a14 [label="returnTypeRef"]

a1 [label="ValueParameter(name = user)"]

a1 -> a2 [label="returnTypeRef"]

a2 [label="UserTypeRef(qualifier=[String])",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a3 [label="StringConcatenationCall"]

a3 -> a4 [label="argumentList"]

a3 -> a13 [label="typeRef"]

a4 [label="ArgumentList"]

a4 -> a5 [label="arguments"]

a4 -> a7 [label="arguments"]

a5 [label="ConstExpression(value=\"Hello, \", kind=String)"]

a5 -> a6 [label="typeRef"]

a6 [label="ImplicitTypeRef",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a7 [label="FunctionCall"]

a7 -> a8 [label="explicitReceiver"]

a7 -> a11 [label="calleeReference"]

a7 -> a12 [label="typeRef"]

a8 [label="QualifiedAccessExpression"]

a8 -> a9 [label="explicitReceiver"]

a8 -> a10 [label="typeRef"]

a9 [label="SimpleNamedReference(name=user)"]

a10 [label="ImplicitTypeRef",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a11 [label="SimpleNamedReference(name=toString)"]

a12 [label="ImplicitTypeRef",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a13 [label="ResolvedTypeRef(=kotlin/String)",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

a14 [label="ImplicitTypeRef",style=filled,color=lightgrey]

}

This structure no longer contains references to the original source code. Keywords are replaced with specific nodes, and comments, parentheses, colons, and other syntactical details are dropped altogether.

In the new K2 Frontend, this step is called Raw FIR Builder.

FIR (Front-end Intermediate Representation) is a mutable tree. At this stage, it is called a Raw FIR because not all references are fully resolved yet (e.g., ImplicitTypeRef instead of ResolvedTypeRef).

The Raw FIR undergoes several FIR phases during which it is transformed into a complete FIR tree with all the necessary semantic information added.

- The compiler performs several desugarings:

- Replace

ifexpressions withwhenexpressions. - Convert

forloops intowhileloops withiterators. - Replace destructing declarations with multiple separate declarations.

- Replace

operatorfunctions (e.g.,[],+,+=) with explicit calls. - …

- Replace

- Resolve imports

- Resolve super types

- Resolve sealed class hierarchies

- Resolve types

- Resolve bodies for functions with implicit return type

- Resolve bodies for functions

- …

Check out all the FIR phases.

After all the stages are completed, we obtain a complete FIR filled with all the semantic information required for the Backend to convert it to an executable program.

Check out The New Kotlin K2 Compiler: Expert Review on YouTube for a detailed explanation of the K2 compiler and the FIR resolution phases.

In the old Frontend, the compiler reuses the PSI tree structure as-is and stores semantic information in a separate structure called BindingContext.

Check out a visual representation of BindingContext (starting from page 29).

This BindingContext is essentially just a huge hashmap. The performance implications of storing all semantic information in the BindingContext were a primary reason for the rewrite of the Kotlin Frontend.

In the old Frontend, there is no IR generation step. The PSI tree and the BindingContext are passed directly to the Backend.

IR generation

During the IR generation phase, the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) from the previous step is transformed into an Intermediate Representation (IR).

The IR does not follow a single structure across all languages. Some languages might use graphs, others might use tuples, and some might use stacks.

Generally, IR serves as an abstracted representation that is closer to CPU-level architecture.

Check out Intermediate Representations.

In the early versions of the Kotlin compiler, there was no IR generation phase at all.

Now, this stage is effectively part of the Backend of the Kotlin compiler.

Machine-independent optimizations

The compiler performs a series of optimizations and transformations on the IR that are independent of the target machine code representations. These optimizations aim to improve the efficiency and performance of the generated code without considering the specifics of the underlying hardware.

Such optimizations may include:

- Remove dead code

- Simplify constant expressions

- Deduplicate repeated expressions

- Move static code outside of loops and functions

- Simplify language constructs

- Desugaring

- …

In Kotlin, this is commonly referred to as Lowerings.

Common Lowerings include:

- FlattenStringConcatenationLowering

- TailrecLowering

- SingleAbstractMethodLowering

- EnumWhenLowering

- KotlinNothingValueExceptionLowering

- LateinitLowering

- …

The platform-specific Lowerings include:

The result of this phase is referred to as Lowered IR.

Code generation

The code generation phase creates an executable that can run on a specific platform. At this point, the executable might still require some optimizations.

For example, for the following Kotlin function:

fun hello(user: String) = "Hello, $user"

would be compiled into the following Java bytecode:

public final static hello(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/String;

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible

// annotable parameter count: 1 (visible)

// annotable parameter count: 1 (invisible)

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible, parameter 0

L0

ALOAD 0

LDC "user"

INVOKESTATIC kotlin/jvm/internal/Intrinsics.checkNotNullParameter (Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/String;)V

L1

LINENUMBER 1 L1

NEW java/lang/StringBuilder

DUP

INVOKESPECIAL java/lang/StringBuilder.<init> ()V

LDC "Hello, "

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/StringBuilder.append (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;

ALOAD 0

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/StringBuilder.append (Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/StringBuilder.toString ()Ljava/lang/String;

ARETURN

L2

LOCALVARIABLE user Ljava/lang/String; L0 L2 0

MAXSTACK = 2

MAXLOCALS = 1

In Kotlin, depending on the compiler used, the result may be machine code (via LLVM), Java bytecode (via ASM), or JavaScript code.

Machine-dependent optimizations

As the final step, depending on the target platform (x86, ARM, Java bytecode, JavaScript, etc.), the compiler may perform additional optimizations specific to that platform. These optimizations directly manipulate the machine code, bytecode, or JavaScript code rather than the IR.

Kotlin compiler evolution

Over the years, the Kotlin compiler has evolved dramatically. Early versions of the Kotlin compiler supported only the JVM target and could be compiled only to Java bytecode. (stable since version 1.0)

Later, support for JavaScript target was, added but Kotlin/JVM and Kotlin/JS backends remained completely separate. (stable since version 1.3)

Kotlin/Native backend, instead of generating the machine code directly, utilizes the LLVM toolchain—an open-source project also used by languages such as C, C++, Haskell, Rust, and Swift.

This led to the migration of Kotlin/JVM and Kotlin/JS compilers to an IR-based implementation as well. The IR-based Kotlin/JVM stabilized in 1.5, and the IR-based Kotlin/JS stabilized in 1.8.

The IR generation, machine-independent optimizations, and the resulting IR structure are consistent for all IR-based backends.

The K2 Frontend stabilized in 2.0. IR-based backends are capable of accepting either PSI + BindingContext or FIR.

Check out Current stability of Kotlin components.

Program Structure Interface (PSI)

The Program Structure Interface, commonly referred to as just PSI, is the layer in the IntelliJ Platform responsible for parsing files and creating the syntactic and semantic code model that powers so many of the platform’s features.

Created by JetBrains, PSI was originally created for the IntelliJ platform to enhance the IDE experience when working with different languages.

It allows for interfacing between different languages, such as navigating between Java and Kotlin source code or even referencing Version Catalog declarations in .toml files from Gradle Kotlin scripts. This capability is one of the strengths of IntelliJ-based IDEs.

While JetBrains IDEs use PSI to highlight code in Java, C, Python, XML, and even Markdown, their compilers (if applicable) do not rely on PSI. However, the same PSI structure used by the IDE is also utilized by the Kotlin compiler, enabling the IDE to directly reuse the Kotlin compiler’s Frontend.

Check out the PsiViewer plugin for IntelliJ-based IDEs.

Highly recommend Simon Ogorodnik’s Kotlin Compiler slides as a detailed deep dive into the inner workings of the Kotlin compiler.

What Everyone Must Know About The NEW Kotlin K2 Compiler is basically a high-level overview of this article.

Crash Course on the Kotlin Compiler by Amanda Hinchman-Dominguez is a quick recap of the Kotlin compiler structure and how compiler plugins work.

Exploring Kotlin IR. At the time of writing this article… | by Brian Norman | Medium

Are there some documents about pseudo? - Support - Kotlin Discussions