Private interfaces

Whenever a concrete implementation of an interface is neeed, people sometimes choose to implement the interface by the enclosing class where they intend to use the interface, instead of creating a new object implementing the interface.

Examples

Before discussing which approach is better or worse, let’s have a look at two simple examples to get a better idea of what I mean.

Fragment example

class InboxFragment : Fragment(), InboxAdapter.Listener {

private val adapter = InboxAdapter(this)

override fun onMessageClicked(messageId: Long) {

// Do something with the messageId

}

}

We need to pass a callback to InboxAdapter through which we will be notified when the user selects a message. We can implement the callback interface by the Fragment and pass the instance of this as the callback.

Compare it to creating an anonymous class implementing the interface:

class InboxFragment : Fragment() {

private val adapter = InboxAdapter(object : InboxAdapter.Listener {

override fun onMessageClicked(messageId: Long) {

// Do something with the messageId

}

})

}

ViewModel example

Another sample I’ve been seeing quite often on the internet is implementing CoroutineScope by a ViewModel to be able to conveniently launch new coroutines anywhere in the scope of the ViewModel.

class InboxViewModel : ViewModel(), CoroutineScope {

override val coroutineContext = Job() + Dispatchers.Main

private fun processData() {

launch {

// Do some processing

}

}

}

Again, compare it to an anonymous class:

class InboxViewModel : ViewModel() {

private val scope = object : CoroutineScope {

override val coroutineContext = Job() + Dispatchers.Main

}

private fun processData() {

scope.launch {

// Do some processing

}

}

}

Consequences

You might say, “So what? Both versions work fine?!” It may just look like a matter of taste but it has one non-obvious consequence:

All methods defined by the interface are now part of public API of the class.

This might not look like a big deal, and in most of the situations you are probably right. The program will, indeed, run the same with either of the approaches. But it is not always only about the final instructions that are performed by a CPU.

It makes development harder.

Increased complexity

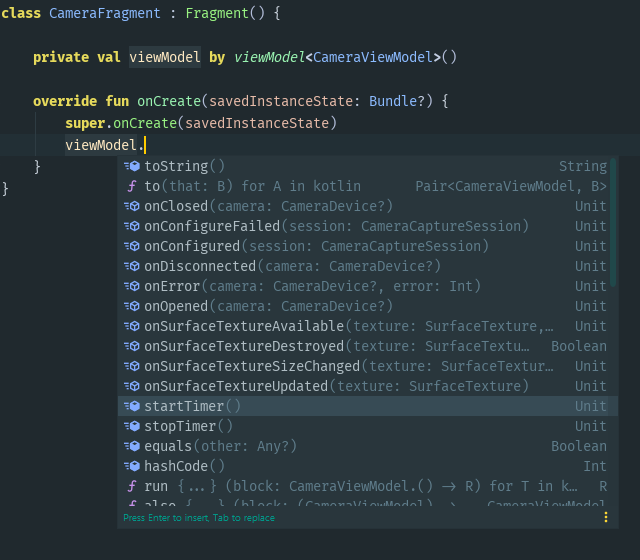

Our examples are trivial, but imagine working with a more complex class. For example, a class that implements CameraCallbacks that defines 10 methods. Developers using this class have to mentally filter suggestions from code completion when working with this class. Why make it part of public API if it is not meant to be called from the outside?

You can never reduce the visibility of methods defined in an interface.

In some cases, this extends to private API as well – typically in case of callback interfaces. If the class itself is not supposed to call these methods either, why does every other member of the class have access to call those methods?

Breaks encapsulation

In the case where we implement CoroutineScope by ViewModel, the scope is meant to be used to run coroutines private to the class. Interactions within the ViewModel are well unit-tested, and those internal coroutines run as intended.

Later, an ingenuous developer needs to run a coroutine from outside of the ViewModel. He has access to the viewModel so he uses it as a scope to run the coroutine:

class CustomFragment : Fragment() {

private val viewModel: CustomViewModel // also implements CoroutineScope

fun onRefreshClicked() {

viewModel.launch {

// Do some processing that may throw an exception

}

}

}

Just like this, it is possible to unintentionally break the internal state of the ViewModel.

Throwing an exception in the launch block would cancel all other coroutines that were also started in the ViewModel’s scope – including coroutines that were started and their effects observed internally in the ViewModel.

Conclusion

If you need to implement an interface in your class, think twice about who will be consuming the interface.

- If the members of your class are the only consumers, prefer using anonymous classes to encapsulate internal details and prevent other classes from breaking your internal state.

- Use implementation by the encapsulating class only if those who use your class are also consumers of the interface.

This is partially related to Composition over inheritance principle. A topic for another article, perhaps.